The Art of Conversation: 3 Tips for Deeper Connections

Advice for cultivating fruitful conversations and avoiding contention

Conversation is a lost art in the 21st century. I don’t mean the inability to speak articulately or our growing infatuation with devices rather than human beings; although movies like Her and Ex Machina are feeling more portentous by the day. What we’ve lost is the ability to craft meaningful conversations and act as useful interlocutors. Most of our social interactions are filled with the inanity of small talk droning on and on about our weekend, our irritating boss, or the latest news. Chances are you know this experience all too well and where it leads. You leave the coffee shop or restaurant knowing and learning absolutely nothing new. Contrast that with the thrilling experience of an engaging dialogue with a skillful conversationalist. A 30-minute chat with a dear friend or mentor that fills your mind with wonder. One where you each discuss matters of importance, speak fervently, and walk away revitalized rather than sapped from socialization. So what’s the difference? How can you have more conversations like that and less vapid conversations about trivial matters?

The answer lies in mastering the art of conversation; an art Frenchmen François de La Rochefoucauld and Blaise Pascal understood quite well. It’s not just a matter of finding the right companion to engage with — although that makes it much easier — but becoming capable of breathing passion and curiosity into any conversation. Here are three pieces of advice for becoming a better conversationalist and navigating debate in a polarized climate.

1. Listen, Think, Speak

In order to speak well, you must also learn how to listen well. Too often in conversations our attention is imbalanced with excessive focus placed upon what we have to say. And by doing so, we fail to listen, reflect, and consider what’s being expressed to us. As French nobleman and epigrammatic author François de La Rochefoucauld puts it,

“One of the reasons why so few people seem reasonable and attractive in conversation is that almost everyone thinks more about what he himself wants to say than about answering exactly what is said to him. The cleverest and most polite people are content merely to look attentive — while all the time we see in their eyes and minds a distraction from what is being said to them, and an impatience to get back to what they themselves want to say. Instead, they should reflect that striving so hard to please themselves is a poor way to please or convince other people, and that the ability to listen well and answer well is one of the greatest merits we can have in conversation.”

In short, to become a better conversationalist you must master both sides of the court: speaking and listening. You must engage under the presumption that the most interesting thing to be said will not come from your own mouth. Learn to sit back and provide space for silence. In modern settings, most people rush to fill silence within a conversation due to anxiety or fear of awkwardness. In reality, meaningful responses take time and your patience will show that you’re giving your interlocutor’s words careful consideration.

2. Seek To Understand, Not Win

In today’s polarized climate, even the most avoidant person will find themselves in the midst of a heated debate over any number of inflammatory topics. These battles are often lost before they even begin because they are entered with the wrong intentions: to win. But what does winning mean or look like? Overpowering them with rhetoric or vocal volume? Earning more retweets?

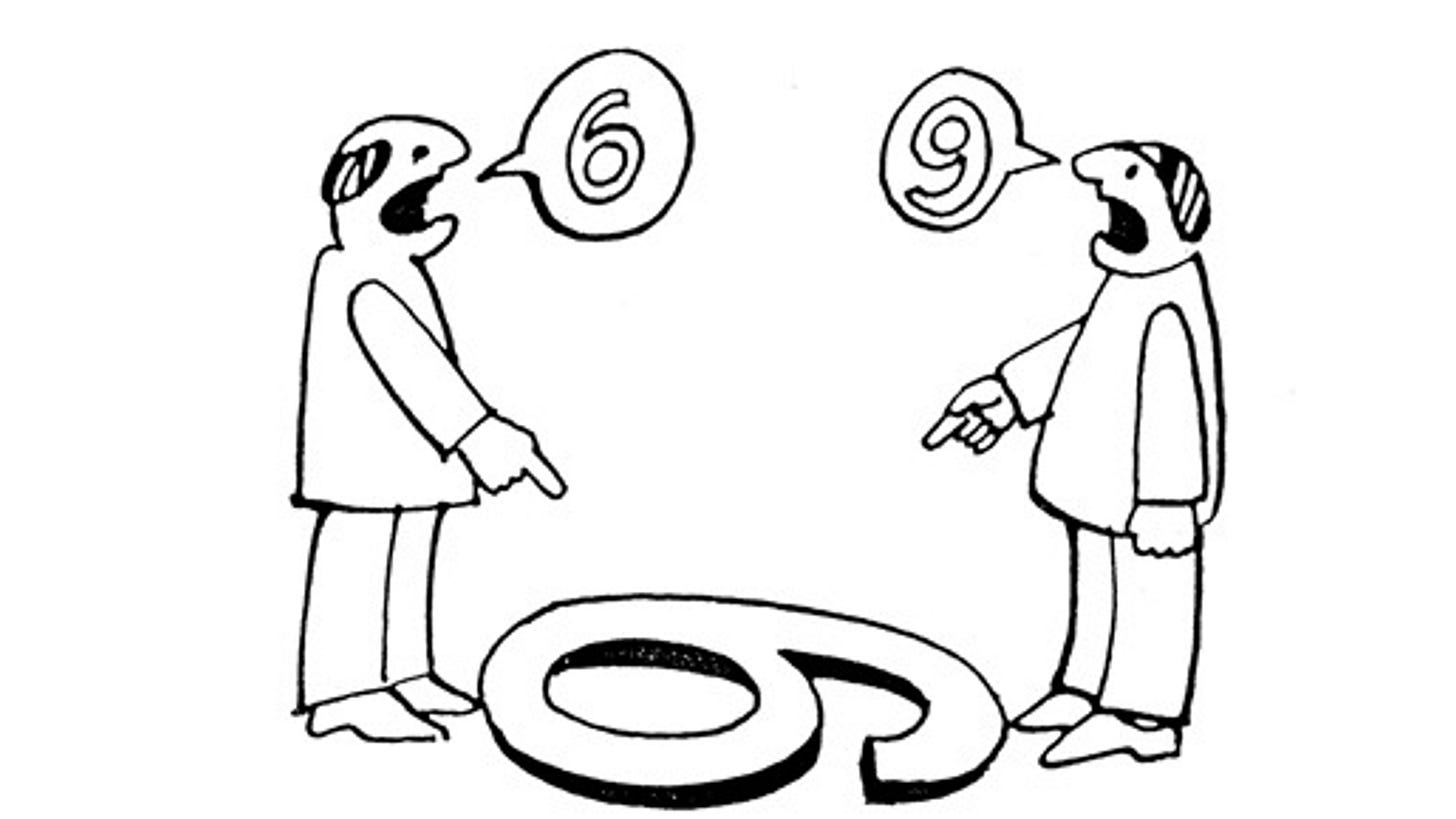

If you are truly to change anyone’s mind on a particular position, you must enter the conversation with empathy and a willingness to view beyond your natural perspective. A desire to not only hear their argument, but view the world through a foreign perspective. Let’s use the famous example below of two gentlemen viewing a number from opposing sides.

From one man’s side the number is a 6 and from the other man’s side it’s a 9. Who’s correct? Both of them are, but not if they remain viewing the number from the position at which they currently stand. If one of them is willing to walk to the other side and view the world through the lens of his interlocutor, he’d understand that he’s not wrong, but merely seeing it from only one angle. You could also refer to the Blind men and an elephant example.