It’s often suggested that ‘hard times create strong men’—a misguided and overused slogan that I debunked in a previous post—but a more a valid claim might be: simple books create simple minds.

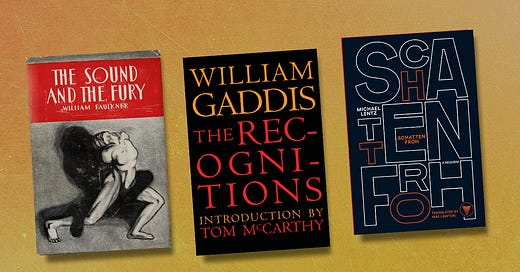

As I juggle both contemporary literature and seminal classics, I naturally find myself stumped by certain books, particularly novels touted as masterpieces. Pivotal works like Ulysses by James Joyce, The Recognitions by William Gaddis, or The Sound & The Fury by William Faulkner are not only held in a sacred space within highbrow literary circles, but have also become infamous for the challenges they pose to readers. They disorient with their style, overflow with allusions, and often deviate from grammatical norms. Frustration inevitably boils over for many readers, leading them to chuck their tattered paperbacks across the room and conclude either that they’re too dumb to understand it or that all the snobs are just plain wrong. Instead of drowning in confusion, I suggest we embrace it.

The Error of Treating Books Systematically

The causes of this vexation with difficult books are plentiful—stemming from both educational instruction and socio-behavioral shifts. We want things to be simple, easy, and convenient. Complex books are the opposite. They make you uncomfortable, demand effort, and typically take extensive hours to read.

In school, we’re taught to view books in an almost formulaic way. Quizzes and tests require us to describe the plot, character descriptions, and extract out key themes. Our teachers tell us what a poem or book actually means. They explain what the author intended, their motifs, etc. Very little room for personal interpretation and open discussion is offered, which inadvertently treats books as something to be solved. Everyone is spoon-fed the same perspective of a work and how it should be understood. So it makes sense that as we become adults and read more complex literature, we get frustrated when we can’t crack the code and pinpoint what it’s all about.

Why Read Hard Books

The value of reading difficult books lies in the fact that they are not meant to be 'solved.' Sure, professors may explain certain references, and you can find thorough analyses online, but by seeking a cookie-cutter understanding of a work, you risk sacrificing true comprehension.

Novels like The Recognitions and The Sound & The Fury aren’t meant to be broken down systematically. They are meant to be experienced. You won’t understand them on the first pass and that’s expected; however, what you will gain is a deep and personal expansion of consciousness. Great literature exposes you to abstract ideas and unconventional angles of viewing the world. Instead of focusing on solving the book and moving on, there’s more value gained by simmering in the stew of confusion instigated by the author. By giving up on difficult books or rushing to a resource for an explanation, you rob yourself of intellectual growth. Just as heavy weights challenge muscles that aren’t yet ready to lift them, complex works stimulate our minds and offer us the opportunity to discover our own answers.

Stop Trying To “Get It”

There is no prize waiting for you once you decode Infinite Jest or The Brothers Karamazov. So much energy and ego is wasted on trying to ‘get it’. Translator Max Lawton put it best in his ‘extroduction’ to Blue Lard when he said:

“A word of advice: You don’t need to understand Blue Lard. In fact, trying too hard to theorize Sorokin’s work or to pin him to any particular ideology risks sinking his whole enterprise. The ideal mode in which to read it is one of wonder, contemplation, and amusement. Let the images and words flow past—do not seek to add unnecessary meaning to them. The quiddity of the work is its own reward.”

This advice extends far beyond the inventive, grotesque works of Vladimir Sorokin. You don’t need to view a piece of literature through the same lens as everyone else. You are no longer confined to a classroom setting and being tested on plot points and primary themes. You are in control of what to pay attention to. Your curiosity defines what matters most or what questions are worth asking. By all means, make use of online resources and group discussions, but maintain your autonomy when it comes to interpretation.

Engaging with a text, specifically ones that perplex you, offers you stimulation that you aren’t likely to find elsewhere in our padded, ready-made society. You’re able to let your own personal experiences and emotions bleed into what you’re reading. Through the confusion and discomfort, you are shaped and intellectually molded by the writer’s ideas. That is precisely what authors like Joyce, Faulkner, Woolf, and others intend. Their works aren’t nuts to be cracked, consumed, and discarded. They are meant to be grappled with, revisited often, and allowed to wrap their roots around you.

The Dangers of Simplicity

To return to my original claim—that simple books may create simple minds—there’s no imperative to torture yourself with inscrutable texts. For many readers, reading is about escapism, enjoyment, or learning. They aren’t looking for riddles to solve and hidden meanings to decipher. And suggesting that these books are more important or valuable because of their complexity carries an air of elitism and pomposity. Rather, I simply want to suggest that books that pose confusion typically present us with unique opportunities for growth. Their resistance to definitive interpretation and their endless layers of meaning offer readers a chance to expand their cognitive abilities and awareness. So before you cast that vexing novel into the corner, give confusion a chance and see what’s on the other side.

I must shoutout to Jack at the Rambling Raconteur for his video on this exact topic, which served as inspiration for the title of this post. These questions surrounding difficult books have been swirling in my mind for a while, but he shared a few key insights that I hope I was able to further build upon.

The key to getting through Gaddis, whether The Recs or JR is working with the audiobook.