5 Life Lessons from Aristotle

Key takeaways from Aristotle's greatest work and how they apply to everyday life

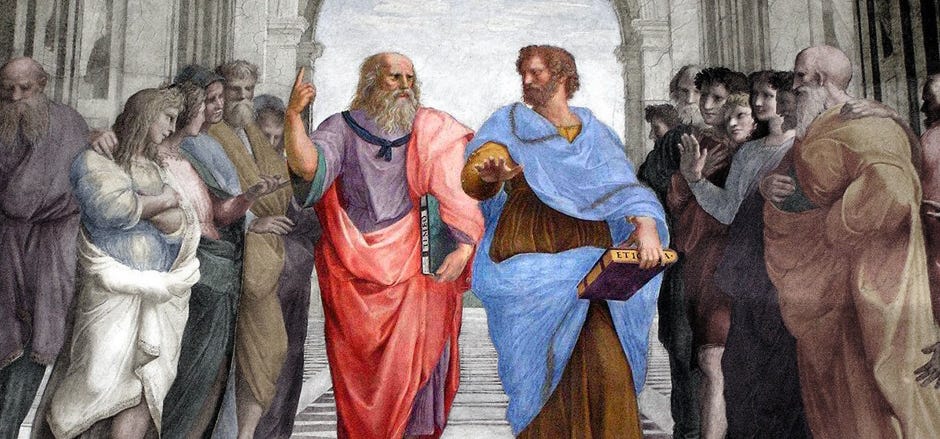

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is an all-encompassing, monumental work that still stands the test of time — and for good reason. Within the text, he provides insight concerning true happiness, virtue, justice, and the dynamic of friendships. Listed below are five lessons I took away from his masterpiece.

1. You Are Your Actions, Not Your Words

“A state of character results from the repetition of similar actions.” (Book II, Chapter 1)

Virtue is not simply defined by how you state yourself to be or through singular actions, but rather a byproduct of the way in which you live. Acting in accordance with any virtue requires habitual action and not selective application. You cannot be deemed brave from one courageous moment, just as you cannot be labeled a coward for a singular lapse of action.

Developing a virtuous character means living out your virtues in all areas of your life consistently and ensuring their stability in the face of adversity or desires.

2. Virtue Is A Mean

“We should observe that theses sorts of states naturally tend to be ruined by excess and deficiency.” (Book II, Chapter 2)

Living within excess or deficiency of any virtue is harmful. Too much bravery leads to arrogance. Too much cowardice leads to inaction. Too much temperance leads to a life absent of pleasure. Too little temperance enables a life overrun by desires.

Through his various examples, Aristotle points out that true virtue is found at the mean; however, the mean is not to be confused with the middle. For example, bravery is closer to brashness than it is to cowardice. In practice, finding the ‘golden mean’ for any virtue requires you to assess the rationality and logic before engaging in any action. You must know when to feel pain and when to feel pleasure. When to be brave and when to be fearful. It cannot be reliant upon your desires or short-term gratification, but dictated by reason and understanding.

3. You Must Love Yourself To Love Others

“For the excellent person is of one mind with himself, and desires the same things in his whole soul. Hence he wishes goods and apparent goods to himself, and achieves them in his actions, since it is proper to the good person to reach the good by his efforts.” (Book IX, Chapter 4)

In order to provide the greatest value to others and nourish the garden of friendship, we must first understand and love ourselves. As the saying goes, ‘you cannot pour from an empty cup’ — which simply expresses the need to initially establish personal value before seeking to engage with others. Attempting to withdraw greater self-worth or happiness from others is a parasitic relationship and not sustainable.

Self-love is not surrendering to one’s misfortunes or negative traits. True self-love is achieved by both mental and physical efforts towards improving one’s well-being. To truly love one’s self, one must not only wish for goodness in their life, but take the necessary actions to achieve such goods. This requires self-responsibility to address negative traits that are within one’s control, such as laziness or gluttony, and correcting them to improve one’s own worth.

4. Less Is More

“A few friends for pleasure are enough also, just as a little seasoning on food is enough.” (Book IX, Chapter 10)

Enduring, valuable friendships are few and far between. When analyzing the dynamic of friendships, Aristotle finds that they typically fall into three categories of value: pleasure, utility, and character. Without expanding too deeply into the context of each, Aristotle argues a great portion of our friendships tend to lean on their pleasantness or usefulness. Due to the nature of those friendships, they typically have strong emotional attachments, but are more prone to rapid dissolution. The reason for this is the value in the friendship is based on ‘what can you do for me’. Once an imbalance of value takes place, the superior party no longer has a need for the relationship and/or the inferior party develops resentment due to the gains of the other.

This leads us to the old adage ‘quality over quantity’ — a concept shared in Aristotle’s quotation above. Friendships based in character or virtue still rely on a mutual advantage for both parties, but are far more stable and capable of enduring conflict. Friends bonded by character share interests, values, and beliefs. It makes more rational sense to engage with someone who values certain goods the same as you do and wishes good upon you. This is not to say that there are no disagreements, but rather they challenge your thoughts in a productive manner that encourages growth and development. In these friendships, you perceive the other as an extension of yourself — loving them as you do yourself. These bonds are much more enduring and capable of overcoming inequality of value because the value isn’t rooted in material goods, utility, or pleasure.

5. Live For Virtue, Not Amusement

“But the happy life seems to be a life in accord with virtue, which is a life involving serious actions, and not consisting in amusement.” (Book X, Chapter 7)

Aristotle effectively points out that neither amusement nor relaxation provide us with a complete happiness. Your purpose within life cannot reside in a vacation or some other temporary pleasure. Instead, a life of complete happiness is one lived with intention and passion — not in enjoyment of a material good or indulgence. Happiness is not a stagnant moment or object, but the process of imprinting our presence and virtues onto the world. A complete happiness is achieved through knowledge of ourselves and continual personal development. Peace and joy are not found on a beach with a cocktail in each hand, but through performing meaningful, virtuous work.

Wrap Up.

To merge these lessons into one cohesive idea, Aristotle believes that in order to achieve complete happiness, one must continuously live in accordance with clear, rational virtues. We must act with prudence to the best of our ability and center our relationships in those who share our values. Lastly, in all of our pursuits we should avoid excesses or deficiencies and seek balance for lasting contentment.